Object-Oriented Programming is well known for allowing different classes to be called with the same interface, via a mechanism called polymorphism. It may seem that the only way to have polymorphism in a program is with objects. In fact, as we are going to see in this article it is possible to have polymorphism without objects via multimethods.

This article has been revised and improved. The revised version is available here

Moreover, multimethods provide more advanced polymorphism than OOP polymorphism as they support cases where the chosen implementation depends on several argument types (multiple dispatch) and even on the dynamic value of the arguments (dynamic dispatch).

This article covers:

- Mimicking objects with multimethods (Single dispatch)

- Multimethods where implementations depend on several argument types (Multiple dispatch)

- Multimethods where implementations depend dynamically on several arguments (Dynamic dispatch)

The essence of polymorphism

In OOP, polymorphism is about defining an interface and having different classes that implement the same interface in different ways.

Let’s illustrate polymorphism with an adaptation of the classic OOP polymorphism example: animal greetings. Let’s say that our animals are anthropomorphic and each of them has its own way to greet, by emitting its preferred sound and telling its name.

Anthropomorphism is our first word that comes from the Greek: it comes from the Greek ánthrōpos that means human and morphē that means form.

In fact, it’s our second word that comes from the Greek. The first one was polymorphism coming from the Greek polús that means many and morphē that means form. Polymorphism is the ability of different objects to implement in different ways the same method.

In Java, for instance, we’d define a IAnimal interface with a greet method and each animal class would implement greet in its own way, like this:

interface IAnimal {

public void greet();

}

class Dog implements IAnimal {

private String name;

public void greet() {

System.out.println("Woof woof! My name is " + animal.name);

}

}

class Cat implements IAnimal {

private String name;

public void greet() {

System.out.println("Meow! I am " + animal.name);

}

}

class Cow implements IAnimal {

private String name;

public void greet() {

System.out.println("Moo! Call me " + animal.name);

}

}

Now, let’s ask ourselves: what is the fundamental difference between OOP polymorphism and a naive switch statement?

Let me tell you what I mean by a naive switch statement. We could, as Data-Oriented programming recommends, represent an animal with a map having two fields name and type and call a different piece of code depending on the value of type, like this:

function greet(animal) {

switch (animal.type) {

case "dog":

console.log("Woof Woof! My name is: " + animal.name);

break;

case "cat":

console.log("Meow! I am: " + animal.name);

break;

case "cow":

console.log("Moo! Call me " + animal.name);

break;

};

}

It makes me think that we have not yet met our animals. For no further due, I am happy to present our heroes: Fido, Milo and Clarabelle.

var myDog = {

"type": "dog",

"name": "Fido"

};

var myCat = {

"type": "cat",

"name": "Milo"

};

var myCow = {

"type": "cow",

"name": "Clarabelle"

};

The first difference between OOP polymorphism and our switch statement is that, if we pass an invalid map to the greet function, bad things will happen.

We could easily fix that by validating input data using JSON Schema

Another drawback of the switch statement approach is that when you want to modify the implementation of greet for a specific animal, you have to change the code that deals with all the animals, While in the OOP approach, we have to change only a specific animal class.

This could also be easily fixed by having a separate function for each animal, like this:

function greetDog(animal) {

console.log("Woof Woof! My name is: " + animal.name);

}

function greetCat(animal) {

console.log("Meow! I am: " + animal.name);

}

function greetCow(animal) {

console.log("Moo! Call me " + animal.name);

}

function greet(animal) {

switch (animal.type) {

case "dog":

greetDog(animal);

break;

case "cat":

greetCat(animal);

break;

case "cow":

greetCow(animal);

break;

};

}

But what if you want to extend the functionality of greet and add a new animal?

Now, we got to the essence of polymorphism! With a switch statement, we cannot add a new animal without modifying the original code, while in OOP we can add a new class without having to modify the original code.

The main benefit of polymorphism is that it makes the code easily extensible.

Now, I have a surprise for you: We don’t need objects to make our code easily extensible. This is what we call: polymorphism without objects. And it is possible with multimethods.

Multimethods with single dispatch

Multimethod is a software construct that provides polymorphism without the need for objects.

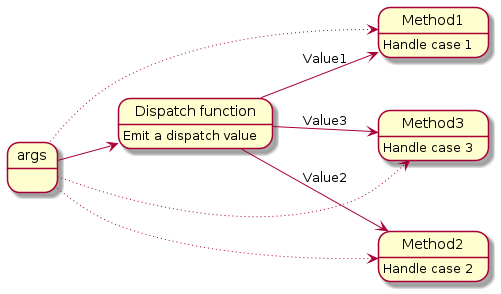

Multimethods are made of two pieces:

- A dispatch function that emits a dispatched value

- A set of methods that provide an implementation for each dispatched value.

A dispatch function is similar to an interface in the sense that it defines the way the function needs to be called. But it goes beyond that as it also dispatches a value that differentiates between the different implementations.

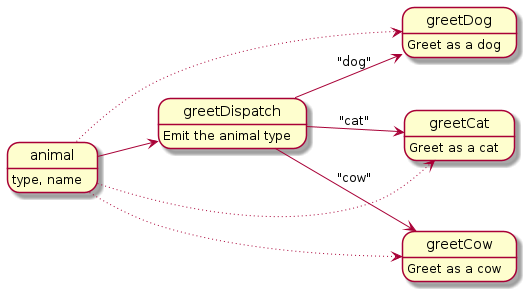

Let me show illustrate how I would implement the animal greeting capabilities using a multimethod called greet. We need a dispatch function and 3 methods. Let’s call the dispatch function greetDispatch: it dispatches the animal type, either "dog", "cat" or "cow".

And each dispatch value is handled by a specific method:

"dog"bygreetDog"cat"bygreetCat"cow"bygreetCow.

In the diagram, there is an arrow between animal and the methods in addition to the arrow between animal and the dispatch function because the arguments of a multimethod are passed to the dispatch function and to the methods.

For now, our multimethod receives a single argument. But in the next section, it will receive several arguments.

Let’s see how a multimethod looks like in terms of code.

We start with the dispatch function greetDispatch: it defines the signature of the multimethod and emits the type of the animal as the dispatched value:

function greetDispatch(animal) {

return animal.type;

}

Now, we need a method for each dispatch value. In our case, we’ll have greetDog for dogs, greetCat for cats and greetCow for cows:

function greetDog(animal) {

console.log("Woof woof! My name is " + animal.name);

}

function greetCat(animal) {

console.log("Meow! I am " + animal.name);

}

function greetCow(animal) {

console.log("Moo! Call me " + animal.name);

}

In the context of multimethods, a method is a function that provides an implementation for a dispatch value.

On the one hand we have the greet dispatch function and on the other hand we have the different greet implementations. How do you wire everything together?

For that, we need a library. For instance, in JavaScript using a library named arrows/multimethod, we call multi to create a multimethod and method to create a method:

var greet = multi(

greetDispatch,

method("dog", greetDog),

method("cat", greetCat),

method("cow", greetCow)

);

The names of the dispatch function and the methods are not really important. But I like to follow a simple naming convention: use the name of the multimethod as a prefix for the dispatch function and the methods and have the Dispatch suffix for the dispatch function and a specific suffix for each method.

Under the hood, the arrows/multimethod library maintains a hash map, where the keys are the values emitted by the dispatch function and the values are the methods. When you call method, the library adds an entry to the hash map and when you call the multimethod it queries the hash map to find the implementation that corresponds to the dispatch value.

In terms of usage, we call a multimethod as a regular function:

greet(myCow);

Multimethods with multiple dispatch

So far, we have mimicked OOP by having as a dispatch value the type of the multimethod argument. But if you think again about the flow of a multimethod, you will discover something interesting: in fact the dispatch function could emit any value.

For instance, we could emit the type of two arguments!

Imagine that our animals are polyglot.

Polyglot comes from the Greek polús meaning much and glôssa meaning language. A polyglot is a person speaking many languages.

Let’s say our animals speak English and French.

We represent a language like we represent an animal, with a map having two fields: type and name.

var french = {

"type": "fr",

"name": "Français"

};

var english = {

"type": "en",

"name": "English"

};

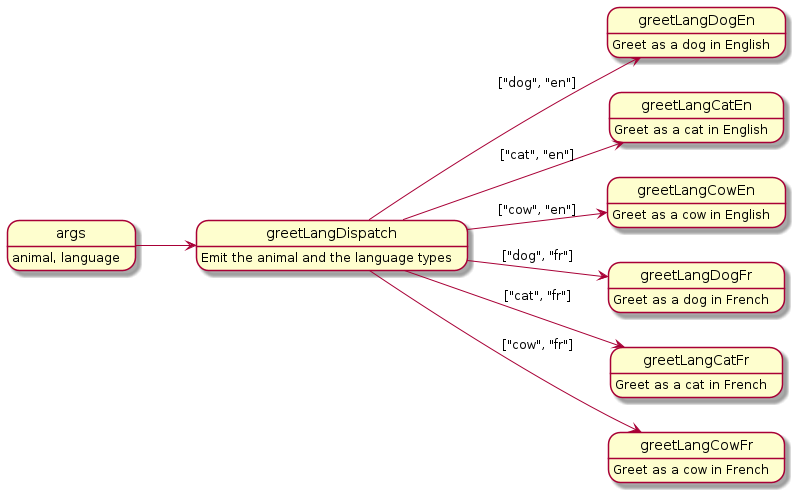

Now, let’s write the code for the dispatch function and the methods for our polyglot animals. Let’s call our multimethod: greetLang. We have:

- one dispatch function

- 6 methods: 3 animals (dog, cat, cow) times 2 languages (en, fr).

But before the implementation I’d like to draw a flow diagram. It will help me to make things crystal clear.

I omitted the arrow between the arguments and the methods in order to keep the diagram readable. Otherwise there would be too many arrows.

The dispatch function is going to return an array with two elements: the type of the animal and the type of the language:

function greetLangDispatch(animal, language) {

return [animal.type, language.type];

};

The order of the elements in the array It doesn’t matter but it needs to be consistent with the wiring of the methods.

Now, let’s implement the 6 methods:

function greetLangDogEn(animal, language) {

console.log("Woof woof! My name is " + animal.name + " and I speak " +

language.name);

}

function greetLangDogFr(animal, language) {

console.log("Ouaf Ouaf! Mon nom est " + animal.name + " et je parle " +

language.name);

}

function greetLangCatEn(animal, language) {

console.log("Meow! I am " + animal.name + " and I speak " + language.name);

}

function greetLangCatFr(animal, language) {

console.log("Miaou! Je m'appelle " + animal.name + " et je parle " + language.name);

}

function greetLangCowEn(animal, language) {

console.log("Moo! Call me " + animal.name + " and I speak " + language.name);

}

function greetLangCowFr(animal, language) {

console.log("Meuh! Appelle moi " + animal.name + " et je parle " + language.name);

}

Take a closer look at the code for the methods that deal with French and tell me if you are surprised to see “Ouaf Ouaf” instead of “Woof Woof” for dogs, “Miaou” instead of “Meow” for cats and “Meuh” instead of “Moo” for cows. I find it funny that that animal onomatopoeia are different in French than in English!

Onomatopoeia comes also from the Greek: ónoma means name and poiéō means to produce. It is the property of words that sound like what they represent. For instance, Woof, Meow and Moo.

Anyway, after we have defined our dispatch function and our methods, we need to wire them altogether in a multimethod, like we did with greet. The only difference that the dispatch values are arrays of strings instead of strings:

var greetLang = multi(

greetLangDispatch,

method(["dog", "en"], greetLangDogEn),

method(["dog", "fr"], greetLangDogFr),

method(["cat", "en"], greetLangCatEn),

method(["cat", "fr"], greetLangCatFr),

method(["cow", "en"], greetLangCowEn),

method(["cow", "fr"], greetLangCowFr)

);

Multiple dispatch is when a dispatch function emits a value that depends on more than one argument.

Let’s see our multimethod in action and ask our dog Fido to greet in French:

greetLang(myDog, french);

Multimethods with dynamic dispatch

Dynamic dispatch is when the dispatch function of a multimethod returns a value that goes beyond the static type of its arguments, like for instance a number or a boolean.

Imagine that instead of being polyglot our animals would suffer from dysmakrylexia.

Dysmakrylexia comes from the Greek dus expressing the idea of difficulty, makrýs meaning long and léxis that means diction. Therefore, dysmakrilexia is a difficulty to pronounce long words.

It’s not a real word, I invented it for the purpose of this article!

Let’s say that when their name has more than 5 letters an animal is not able to tell it.

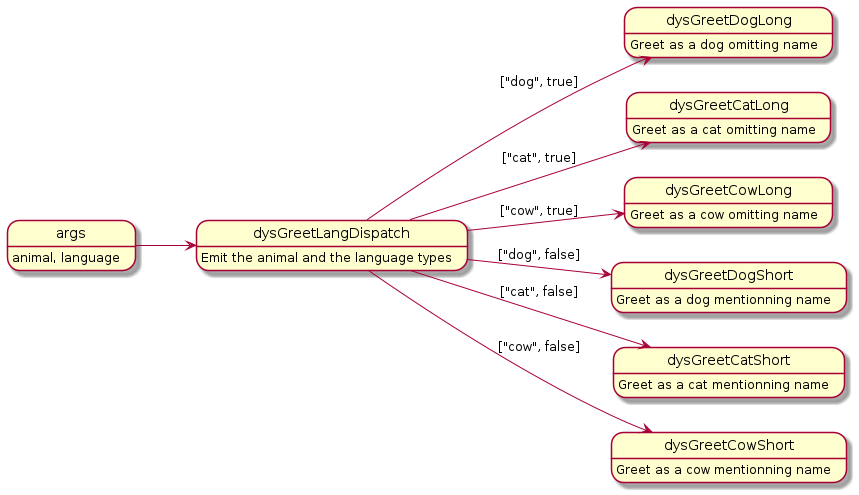

Let’s call our multimethod dysGreet.

Its dispatch function returns an array with two elements: the animal type and a boolean about whether the name is long or not:

function dysGreetDispatch(animal) {

var hasLongName = animal.name.length > 5;

return [animal.type, hasLongName];

};

And here are the methods:

function dysGreetDogShort(animal) {

console.log("Woof woof! My name is " + animal.name);

}

function dysGreetDogLong(animal) {

console.log("Woof woof!");

}

function dysGreetCatShort(animal) {

console.log("Meow! I am " + animal.name);

}

function dysGreetCatLong(animal) {

console.log("Meow!");

}

function dysGreetCowShort(animal) {

console.log("Moo! Call me " + animal.name);

}

function dysGreetCowLong(animal) {

console.log("Moo!");

}

As surprising as it may sound, wiring a multimethod with dynamic dispatch is as simple as wiring a multimethod with static dispatch:

var dysGreet = multi(

dysGreetDispatch,

method(["dog", false], dysGreetDogShort),

method(["dog", true], dysGreetDogLong),

method(["cat", false], dysGreetCatShort),

method(["cat", true], dysGreetCatLong),

method(["cow", false], dysGreetCowShort),

method(["cow", true], dysGreetCowLong)

);

And now, if we ask Clarabelle to greet, she omits her name:

dysGreet(myCow)

Multimethods in other languages

Multimethods are available in many languages, beside JavaScript. In Common LISP and Clojure, they are part of the language. In Python, there is a library called multimethods and in Ruby there is Ruby multimethods. Both work quite like JavaScript arrows/multimethod.

In Java, there is the Java Multimethod Framework and C# supports multimethods natively via the dynamic keyword. However, in both cases, it works only with static data types and not with generic data structures. Also, dynamic dispatch is not supported.

Wrapping up

Multimethods make it possible to benefit from polymorphism when data is represented with generic maps. Multimethods are made of a dispatch function that emits a dispatch value and methods that provide implementations for the dispatch values.

In the simplest case (single dispatch), the multimethod receives a single map that contains a type field and the dispatch function of the multimethod emits the value of the type field. In more advanced cases (multiple dispatch and dynamic dispatch), the dispatch function emits an arbitrary value that depends on several arguments.