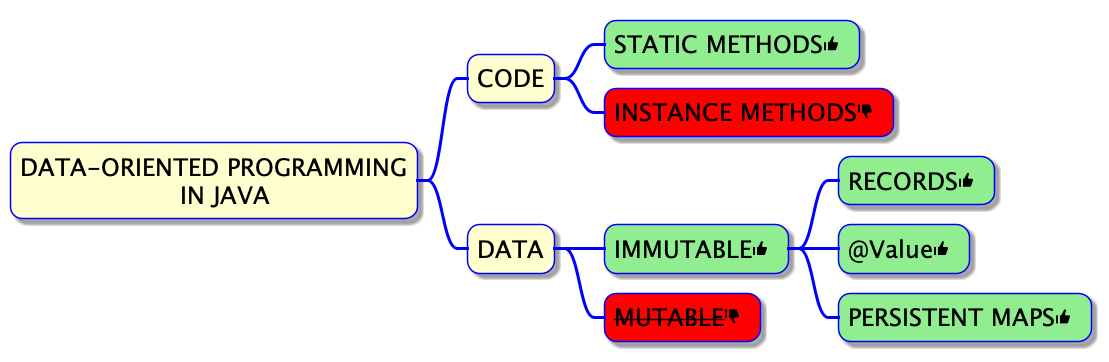

The principles of Data-Oriented programming

The purpose of Data-Oriented programming (DOP) is to reduce the complexity of software systems, by promoting the treatment of data as a first-class citizen.

Concretely, it comes down to the application of 3 principles:

- Code is separated from data

- Data is immutable

- Data access is flexible

Those principles are not new: They have been adopted in one way or another by the Java community over the years through various design patterns (e.g. Entity component system) and smart libraries that leverage Java annotations (e.g. Project Lombok).

However, I believe that the combination of those 3 principles makes a whole that is greater that the sum of its parts, in the sense that software systems built on top of DOP principles tend to be less complex. In my book Data-Oriented programming, I am exploring in greater details how to apply the principles of DOP in the context of a production software system.

In the present article, I am going to illustrate how to apply the principles of DOP in Java.

Separating code from data in Java

Suppose we want to build a library management system with the following requirements:

- Two kinds of users: library members and librarians

- Users log in to the system via email and password.

- Members can borrow books

- Members and librarians can search books by title or by author

- Librarians can block and unblock members (e.g. when they are late in returning a book)

- Librarians can list the books currently lent by a member

- There could be several copies of a book

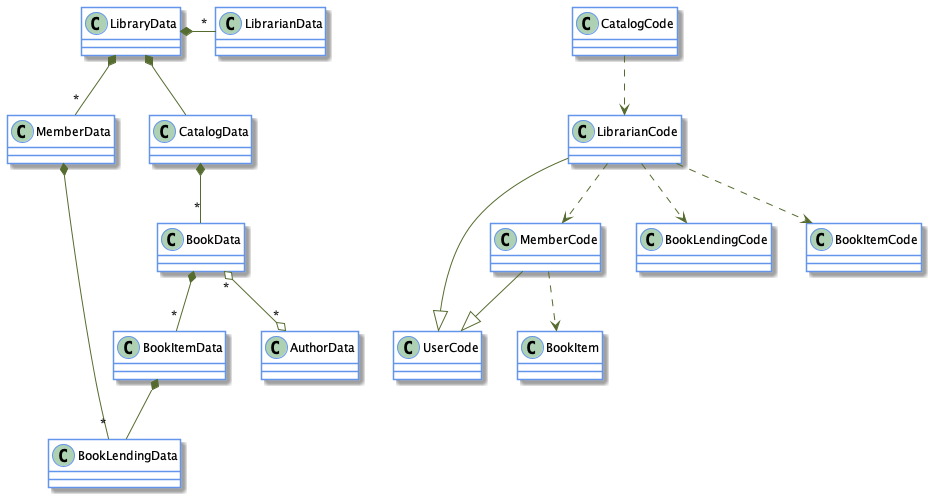

A possible (naive) classic Java design for such a system would be made of the following classes:

Library: The central part for which the system is designedBook: A bookBookItem: A book can have multiple copies, each copy is considered as a book itemBookLending: When a book is lent, a book lending object is createdMember: A member of the libraryLibrarian: A librarianUser: A base class forLibrarianandMemberCatalog: Contains list of booksAuthor: A book author

A possible class diagram (eluding the details about members and methods) would be something like this:

Of course, a Java expert would probably comes up with a smarter design, leveraging some smart design patterns.

Now, I’d like to illustrate how the application of DOP Principle #1 naturally leads to a simpler design, without involving any design patterns. We are going to split each class of our system in two classes:

- A code class with static methods only

- A data class with members only

The result is a diagram made of two disjoint diagrams:

- Data classes on the left

- Code classes on the right

Don’t you agree that the resulting diagram is less complex than the previous one?

The cool think is that applying Principle #1 doesn’t require being a Java expert. Of course, the combination of smart design patterns and DOP Principle #1 would lead to an even better design.

How to represent immutable data in Java

The benefits of applying DOP Principle #2 about data immutability in Java have been widely discussed. Basically, it comes down to:

- Thread safety

- Absence of hidden side-effects

- Ease of caching

- Prevention of identity mutation

The interesting question is: How do we represent immutable data in Java. There are mainly, three approaches:

- Immutable classes (boilerplate code avoided via Java annotations)

- Data records (available since Java 14)

- Persistent hash maps

Representing data with immutable classes

Immutable classes, have no methods and the members cannot be modified.

Writing manually for each immutable class of our system the appropriate constructors, getters, equals(), hashCode() and toString() involves lot of boilerplate code. We could avoid the boilerplate code using a Java annotation like @value annotation from Project Lombok.

Here is how we could represent the catalog data of our library management system using @value annotation:

@value public class AuthorData {

String name;

List<String> bookIds;

}

@value public class BookData {

String title;

String isbn;

Integer publicationYear;

List<String> authorIds;

}

@value public class CatalogData {

String items;

Map<String, BookData> booksByIsbn;

Map<String, AuthorData> authorByIds;

}

As an example, here is how we would instantiate data of a catalog with a single book: Watchmen.

var watchmen = new BookData("Watchmen",

"978-1779501127",

1987,

List.of("alan-moore", "dave-gibbons"));

var alanM = new AuthorData("Alan Moore", List.of("978-1779501127"));

var daveG = new AuthorData("Dave Gibbons", List.of("978-1779501127"));

var booksByIsbn = Map.of("978-1779501127", watchmen);

var authorsById = Map.of("alan-moore", alanM,

"dave-gibbons", daveG);

var catalog = new CatalogData("books", booksByIsbn, authorsById);

And we display in upper case the id of the first author of Watchmen like this:

catalog.booksByIsbn().get("978-1779501127")

.get(0).toUpperCase(); // "ALAN-MOORE"

Representing data with records

Java language maintainers acknowledge the need to provide immutable data representation at the language level. Java 14 introduced the concept of a record that provides a first-class means for modelling data-only aggregates.

Here is how our data model would look like with records:

public record AuthorData (String name,

List<String> bookIds) {}

public record BookData (String title,

String isbn,

Integer publicationYear,

List<String> authorIds) {}

public record CatalogData (String items,

Map<String, BookData> booksByIsbn,

Map<String, AuthorData> authorByIds) {}

Records are instantiated like immutable classes:

var watchmen = new BookData("Watchmen",

"978-1779501127",

1987,

List.of("alan-moore", "dave-gibbons"));

var alanM = new AuthorData("Alan Moore", List.of("978-1779501127"));

var daveG = new AuthorData("Dave Gibbons", List.of("978-1779501127"));

var booksByIsbn = Map.of("978-1779501127", watchmen);

var authorsById = Map.of("alan-moore", alanM,

"dave-gibbons", daveG);

var catalog = new CatalogData("books", booksByIsbn, authorsById);

And we display in upper case the id of the first author of Watchmen like this:

catalog.booksByIsbn().get("978-1779501127")

.get(0).toUpperCase(); // "ALAN-MOORE"

Read more about Java records in this article.

Persistent string maps

Now comes the esoteric part that might cause you to feel uncomfortable as a Java developer.

Instead of representing data with a layout that is statically defined in our code base, we could represent data with hash maps without specifying data layout at all.

The advantage of this approach is that it makes data access and data manipulation flexible. Of course, it has to trade off flexibility for type safety. My purpose here is not to convince you that this is the way you should represent data in Java. My humble purpose is to suggest that a dynamic approach to data is applicable in Java. Hopefully, it will motivate Java experts to explore if it makes sense to promote the dynamic data approach in Java.

Let’s see first how we could instantiate our catalog data using native Java immutable string maps and lists:

var watchmen = Map.of("title", "Watchmen",

"isbn", "978-1779501127",

"publicationYear",1987,

"authorIds", List.of("alan-moore", "dave-gibbons"));

var alanM = Map.of("name", "Alan Moore",

"bookIds", List.of("978-1779501127"));

var daveG = Map.of("name", "Dave Gibbons",

"bookIds", List.of("978-1779501127"));

var booksByIsbn = Map.of("978-1779501127", watchmen);

var authorsById = Map.of("alan-moore", alanM,

"dave-gibbons", daveG);

var catalog = Map.of("items", "book",

"booksByIsbn", booksByIsbn,

"authorsById", authorsById);

The limitation of Java immutable maps is that we cannot update them efficiently. Creating a new version of the catalog data (e.g. updating the publication year of a book) would require to copy the whole map. Fortunately, there is this computer science thing called persistent data structures that makes it possible to update immutable data structures efficiently both in terms of memory and computation.

There is a Java library named Paguro that provides efficient persistent data structures in Java.

Instantiating our catalog with Paguro is a bit more verbose as we have to wrap key-values pairs in maps with tuples:

var watchmen = map(tup("title", "Watchmen"),

tup("isbn", "978-1779501127"),

tup("publicationYear", 1987),

tup("authorIds", vec("alan-moore", "dave-gibbons")));

var alanM = map(tup("name", "Alan Moore"),

tup("bookIds", List.of("978-1779501127")));

var daveG = map(tup("name", "Dave Gibbons"),

tup("bookIds", List.of("978-1779501127")));

var booksByIsbn = map(tup("978-1779501127", watchmen));

var authorsById = map(tup("alan-moore", alanM),

tup("dave-gibbons", daveG));

var catalog = map(tup("items", "book"),

tup("booksByIsbn", booksByIsbn),

tup("authorsById", authorsById));

With string maps (both Paguro and Java), we cannot easily access nested data in our catalog:

catalog.get("booksByIsbn").get("978-1779501127j")

.get("authorIds").get(0).toUpperCase(); // throws an exception

The problem is that inside the catalog map, we have values of different types:

itemsis a stringbooksByIsbnandauthorByIdsare maps

In order to be able to access the value associated with booksByIsbn as a map, we have to do a static cast:

var booksByIsbn = (Map<String,Map>)catalog.get("booksByIsbn");

booksByIsbn.get("978-1779501127") // returns a map

And we have to do it multiple times until we get to the value we are interested in:

((String)

((Map<String,List>)

((Map<String,Map>)catalog.get("booksByIsbn"))

.get("978-1779501127"))

.get("authorIds")

.get(0))

.toUpperCase(); // "ALAN-MOORE"

I told you it would be esoteric!

We could alleviate a bit the awkwardness of this approach by adding getter methods in our map for each type of value (similar to Apache Wicket value maps). Then it would look a bit less awkward to access a value in a nested map, as the casting is hidden in the getter:

catalog.getAsMap("booksByIsbn")

.getAsMap("978-1779501127")

.getAsList("authorIds")

.getAsString(0)

.toUpperCase(); // "ALAN-MOORE"

We could move one step further and implement nested value getters (similar to get-in in Clojure or Lodash get in JavaScript). Then, we could access a nested value in a very concise way:

catalog.getInAsString(vec("booksByIsbn",

"978-1779501127",

"authorIds",

0))

.getUpperCase(); // "ALAN_MOORE"

Let me conclude this article by mentioning potential benefits that the dynamic data approach would provide if it is adopted by the Java community.

Potential benefits of a dynamic data approach

Weak dependency between code and data

When a piece of code manipulates data represented in a generic way it doesn’t have to include the class that defines the layout of the data. The only information that is required is the name of the fields to be manipulated.

Information path

When we represent the whole data of the system in a generic way, each piece of information of the system is accessible via its information bath: A list of keys and indexes that describe the path to the information.

Serialization without reflection

When data is represented with hash maps and lists, we can serialize it (e.g. JSON serialization) in a natural way without using reflection or any custom annotation.

Manipulate data with general-purpose functions

When data is represented in a generic way, we are free to manipulate it with a rich set of general-purpose functions. Let me mention two quick examples:

Rename keys

Suppose we want to send book information over the wire with a slight modification: the title field should be renamed to bookTitle. In a non-dynamic approach to data, we would have to create another class BookWithBookTitle (it would be hard to come up with a good name!).

In a dynamic data approach, we could write a general purpose function renameKey(). The cool thing is that renameKey() wouldn’t be coupled to book data. As a consequence, we could use renameKey() to rename the field of author data.

Merge data

Suppose, we’d like to enrich book information with data from Amazon and GoodReads. In a non-dynamic approach we’d probably need to create classes or records for AmazonBookInfo, GoodReadsBookInfo and EnrichedBookInfo. Anyway, we’d have to write custom code that merges information from Amazon and GoodReads.

In a dynamic data approach, we could leverage a general purpose merge function that works on an arbitrary map.

Conclusion

This article suggested that it would be possible to apply the principles of Data-Oriented programming in Java.

- Code is separated code from data

- Data is immutable

- Data access is flexible

Principles #1 and #2 feel quite natural to Java developers (especially with the addition of Java records). However, Principle #3 feels much less natural.

I hope that by having illustrated the benefits of a dynamic data approach, I have motivated a bit the Java community. Now it’s time for Java experts to take it from there and discover (hopefully in the near future) what is the best way to embrace Data-Oriented programming in Java.